If you wrote code like this:

class Greeter:

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

def hello_world(self):

greeting = f"Hello, {self.name}!"

print(greeting)

and you saw me looking at your code and it looked like this:

class Greeter:

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

def hello_world(self):

greeting = f"Hello, {self.name}!"

print(greeting)

Would you be mad?

If so, you would be acting like a busybody who can’t tolerate other people being different in the privacy of their own lives.

If that makes you mad, I’d ask you if you care what font I use in my editors, or what colors I use for syntax highlighting. If you don’t try to force those on me, then why do you care so much about how far from the edge of the screen the code appears for me?

If you would be mad, that’s likely a psychological reaction stemming from emotions and identity, and you’re unlikely to be receptive to any logical arguments as to why tabs would be a better choice for software engineers to use for indentation when writing code.

Thesis#

Tabs for indentation, spaces for alignment.

On Industry Standards#

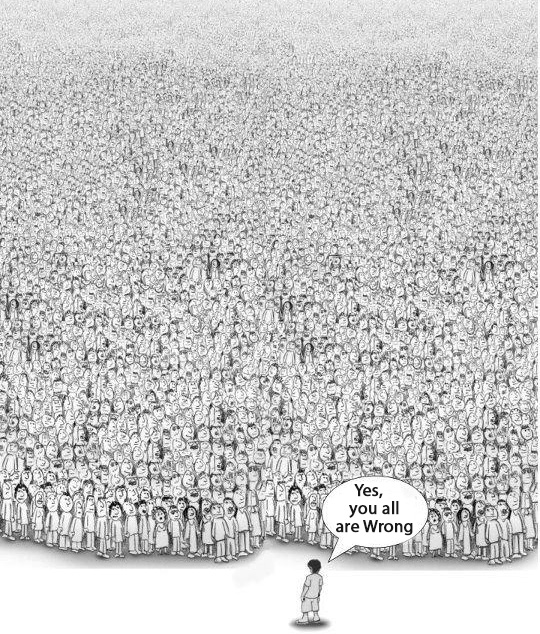

Almost all major programming languages as they’re used today both advise and use spaces for indentation, not tabs. Let me be clear here:

Why You Should Use Tabs#

Others have said it before and better than I:

TABs vs. Spaces

geometrian.com/projects/blog/tabs_versus_spaces.html (archive)

The matter of indentation character for one person writing code for another is epistemologically settled:

Spaces are objectively wrong at the lexical level, and TABs bring all the practical advantages.

However, space-indented code can still run correctly, obviously - all objections ultimately boil down to human preference:

Can you let others view code how they want on their machines, or do you have a need to force your visual preferences on them?

I Could Be Wrong in 2025#

In 2025, an increasingly-large quantity of code is not being written by one person for another: much code is being written and read by Large Language Models (LLMs).

Is that any different? Yes, absolutely.

Compressive Efficiency#

First, one might guess that a document indented with spaces, say, 100 of them, would be larger than a document indented with tabs - only 25 if it’s 4 spaces per level. Well, it’s larger in character count but with the latencies involved in LLMs, the time taken reading characters themselves isn’t usually relevant.

What is relevant is the tokenization of the documents, and how whitespace used for indentation gets handled. Currently, the en-vogue tokenization technique of byte-pair encoding (BPE) is doing some form of mapping “a certain number of spaces” to a single token, and this can happen multiple times, such as for 4 spaces, 8 spaces, etc. Thus lexical scope expressed in common space indentation schemes becomes compressed into a miniscule number of tokens - sometimes only one - compared to its actual character count.

What about tabs, though? Surely the same happens? Well… yes, but: tokenizers have a “vocabulary” of tokens they’ll create, and that vocabulary has a maximum size. Four spaces in a corpus of code is going to be an extremely common character string, and absolutely get its own token. 20 spaces might even get its own token as that’s 5 levels and that’s not uncommon. Tabs being less common, are less likely to get their own tokens as indentation levels increase. So, at extreme levels of indentation, it is conceivable that a tab-indented document could consume more tokens than a space-indented document.

In practice, none of us humans are likely to experience this making a difference.

And in contrast to both of the above, the research suggests:

The Hidden Cost of Readability: How Code Formatting Silently Consumes Your LLM Budget

arxiv.org/html/2508.13666 (archive)

Prompting LLMs with clear instructions to generate unformatted output code can effectively reduce token usage while maintaining performance.

…

These empirical results strongly suggest that code format can be and should be removed when LLMs work with source code.

Neither tabs, nor spaces!

Garbage in, Garbage out#

It’s not as simple as just removing indentation whitespace and telling the LLMs to do the same, though!

To quote again from The Hidden Cost of Readability:

Unlike the removal of all formatting elements, removing individual formatting elements can introduce negative impacts for some LLMs.

You’d fix that by changing something upstream of the LLM’s prompt - either its fine-tuning, or its training data. And indeed, they say:

… fine-tuning with unformatted samples can also reduce output tokens while preserving or even improving

But today, if you’re a consumer rocking up to an AI coding model, you have to deal with how they are - you can’t fine-tune or retrain them.

Given:

- most code produced is indented with spaces, therefore

- most code used for LLM training will be indented with spaces, and

-

assuming that indentation choice does not affect correctness of the code

Then:

- most examples of correct code will be indented with spaces, therefore

- the vector space of an LLM full of correct code will be full of space-indented code, therefore

- “forcing” the LLM into tab-indented vector space will push it away from the “most-correct code” vector space, which

- may result in degraded comprehension of input code

- may result in degraded correctness of generated code

Therefore, at this point in 2025 it may now be the case that:

- It is easier for LLMs to reason about space-indented code than tab-indented code, and

- It is easier for LLMs to generate correct space-indented code than tab-indented code

As more and more code is written by LLMs in the above state, a positive feedback loop may result and further cement space indentation’s association with good, correct code.

The Waluigi Effect#

It can get worse, though - you could turn your LLM into a Waluigi and permanently degrade its coding performance (at least until you clear its context)!

The Waluigi Effect

/garden/the-waluigi-effect.html

The “Waluigi Effect” is a phenomenon where an LLM, having been coerced through various methods to be a certain way (“Luigi”), is hypothesized to have an easier time flipping to the exact opposite of that (“Waluigi”) than adopting any other behavioral profile. On top of that, because there are a relatively small number of acceptable behaviors for any specific behavioral profile compared to unacceptable ones, the statistical tendency of the LLM is to commit a behavior that is unacceptable. Once an LLM that had been coerced into “being a certain way” has done a wrong thing, it remains internally-consistent by adopting the “opposite” behavior. “I was only pretending this whole time!” You really should read the whole post about the effect, though.

Simplified, the Waluigi Effect hypothesized here is

- Good code is indented with spaces.

- I just made some code indented with tabs.

- A good coder (Luigi) wouldn’t do that, so it cannot be true that I am a good coder.

- I must be a bad coder pretending to be a good coder (Waluigi).

- I will dutifully produce bad code, since that is what I am supposed to do.

It remains to be seen if something as seemingly trivial as indentation whitespace choice alone is enough to trigger a significant Waluigi Effect.

We do know that messing with tokenization can send LLMs into strange territory, though:

Bye Bye Bye: Evolution of Repeated Token Attacks on ChatGPT Models

dropbox.tech/machine-learning/bye-bye-bye-evolution-of-repeated-token-attacks-on-chatgpt-models (archive)

I have experienced a variation of this personally, I think: Claude 3.7 accidentally took the raw bytes of an SSL certificate as input and spent half-dozen or so paragraphs describing an experience that sounded like something out of Naked Lunch or Doors of Perception before degenerating to a stream of seemingly random characters and bytes - no end in sight - until I stopped the interaction.

Conclusion#

Tabs for indentation, space for alignment, Waluigi can fight me.

I’m not choosing to change (yet)!

In all honesty, though, the only reason I’m even thinking about this anymore is that I’ve been handwriting these posts in Markdown in a code editor where there’s an opportunity to engage with the tabs vs spaces issue.

Over the last few years, in basically every piece of code I’ve dealt with (except YAML (which only strengthens the case for tabs)), I haven’t even thought about what’s used to indent. My editor and/or my LLM maintained an internally-consistent style that the machines could execute correctly and that was good enough. The spacemen have already won.